| |

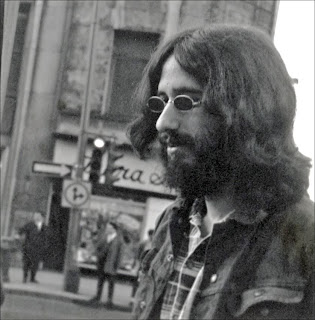

| Brian Nation in early 60s (photo: Anna McGarrigle) |

Rusty normally gave me my pay envelope but this particular Friday he said Bernstein had it. The Boss. He wanted to see me for some reason. So there I was on the carpet when I should have been halfway home on the bus by now.

“Brian, what’s with the hair?”

Seven or eight months earlier, on the Monday morning of my new job, getting myself ready, something to eat and put on my shoes, washing up, I decided no more shaves, no more haircuts, and took the bus to Pointe St Charles. The first few days were hell. The work was hard, and the days were hot. I sweated like a pig and drank coke after coke, which only made it worse. I hated the work at first, but I eventually got used to it and even liked it eventually. I was in a scrap metal yard, moving and sorting tons of steel and iron from one place to another, loading or unloading trucks, sorting and piling aluminum, brass, copper, lead. Trucks pulled into the yard and I’d hop into the passenger seat and we’d drive to the scales a few blocks away. We’d weigh the truck, drive back to the yard, unload it by hand, then go back and weigh it again and the difference was what the driver got paid for. I drank cokes and learned to smoke on that job. Those first days I worked with Roy, a black guy from the States who talked nonstop about sex and told me I had to smoke because if you took a break the boss would say whaddya standing around for?, but if you stopped for a cigarette he’d see you were just having a smoke — a guy had to smoke. He rolled his own (takes even longer, he explained) and started rolling for me, too. The next day I bought my own makings.

It wasn’t a bad job. I sweated, got dirty, wore a hard hat. Traded jokes with the guys, mostly poor French Canadians and a couple of immigrant labourers, like the Italian Bruno who barely spoke English or French and was strong as an ox. Within a few months I worked my way up the ladder of scrapyard success. The Boss and his manager, Rusty, figured I had brains and when things were slow had me help out in the office or organizing the yard. Lucien was the foreman and lived in a poor slum shack next to the yard but pretty soon I was taking on more of his duties as he really wasn’t all that bright, though a good worker.

They had a used machinery side to the business, too. A warehouse filled with motors, air compressors, etc. It was all a mess so they asked me to figure out what was where and to keep it all in a book. I devised a system so that when someone came in looking, for example, a 5-horsepower generator I could find it in a minute and tell them what they paid for it so they could add their markup and make money.

Meanwhile my beard grew and my hair reached my shoulders. I took a hell of a lot of ribbing from everyone but didn’t mind. After all it was my own choice. I got called Jesus a lot. This is 1962, remember. I did my job, got along with everyone, laughed off the jokes, so I was just this weird guy with long hair and that was all there was to it. Till Bernstein gets me in his office.

“Brian, what’s with the hair?”

“What about it?”

“You can’t have hair like that. The beard we don’t mind. Just trim it. But the hair’s not acceptable.”

“Why not?”

“We get comments from our customers. Doesn’t look good.”

“I know your customers. We get along fine. They kid me but no one really cares. It’s a junkyard.”

“Listen, Brian. You got more on the ball than anyone else here. You’re smart and do a good job.

We’d like to promote you. Make you the foreman.”

“I don’t want to be foreman. Lucien’s the foreman and needs it more than me. He’s got a family to feed.”

“Eventually we’ll make you a salesman — send you out on the road.”

“Thanks, Mr. Bernstein, but I like it fine where I am. I like the job, like the guys I work with. I don’t want a promotion and definitely don’t want to be a traveling salesman.”

This floored Bernstein. He was speechless for a moment. Not want a promotion? On the road with car, expense account, whores, drunken parties and conventions? Success, progress, money? I sensed his brain struggling to comprehend, then give up.

He handed me the pay envelope.

“Listen, get your hair cut or don’t bother coming in Monday.”

Which I didn’t.

Six months later I was broke and had been for some time. I met this guy, Petur. A friend of Karen’s. He needed a place so I let him stay at mine a while. He knew I had unemployment money coming but I had to get the book from my ex boss. In those days every week you worked your boss put a stamp in the book. You paid half, the boss paid half. Probably two bucks a week back then.When you were out of work you took your book to the unemployment office and they gave you a weekly cheque for every stamp in it. It was just laziness that kept me from going to get the book all these months. Even broke I was having too much fun, partying most nights and sleeping too late to make it to the scrap yard before closing. Petur got work and paid part of my rent ($40 a month total) and thought I was crazy to be broke when I had this money coming, so he got me up one day and dragged me to the bus stop and took me out to Point St Charles. Rusty got me my book and told me, with a hint of resentment in his voice, that no one could figure out my stock system or keep shit organized as I had. Bernstein came out of his office, surprised to see me.

“How are you, Brian?”

“Doing great, thanks.”

“Have you found another job?”

“Nope.”

“Listen . . . we’d like you to come back to work here.”

My hair was even longer than when I left.

“Thanks, Irving, but no thanks.”